"Real knowledge is to know the extent of one's ignorance." — Confucius

|

T E A C H I N G |

As a historian at Western Illinois University, I’m first and foremost a teacher. And as such I offer the numerous courses listed below. But if you’re interested in taking a specific course, you may first want to consider my views on teaching history and how I tend to do it. As Elizabeth Green writes in the new book, Building a Better Teacher, "Education is not the filling of a pail but the lighting of a fire." If indeed this is the case, it poses a critical question: what's the point of lighting the fire? From my perspective the purpose of all education is to answer another kind of question—the one that Socrates posed over and over again: "How should we live our lives?" Much of our university industrial complex today seems satisfied to conclude that we best live our lives by obtaining a big, fat paycheck. I have a different idea, and it's highly consistent with my department’s mission “to help students become informed citizens” and “enable them to excel in their chosen careers.” The first step in determining how to live is to examine ourselves, know who we are, comprehend the world around us, and thus make sense of our reality. To do this, though, we must first know from where we came and where we now seem to be headed. Enter the study of history, which enables us to do exactly that. The other question arising from the analogy of education as the lighting of a fire is this: how do we get the blaze going? I once knew an academic provost who summarized what teaching was all about to his faculty. He said it was simple: the teacher and the student read the same text; discuss it in class; and in the process develop a fruitful and mutually sustaining dialogue. It may seem trite, but ever since I first heard this dictum about fifteen years ago I have come back to it again and again. For much of my teaching career I relied on technology, using both texts and images via PowerPoint and other computer applications. A few years ago, however, I began to doubt that this technology was helping students achieve the objectives of knowing themselves and from where they came. I specifically started to question the notion that some students were “visual learners,” while others were not. Thanks to the recent work of cognitive psychologists, we now know that this and other popular educational ideas are not living up to their claims. Having recently shifted what I do in the classroom, I’m now much more apt to use primary historical sources in a course, particularly written documents. I still lecture (though not as much as I use to), but increasingly I have tried to develop classroom dialogues about sources and texts assigned in a course. Once more, then, it all goes back to Socrates. I’ve always been insistent on assigning much reading and writing in my courses. To me student reading and writing are the veritable bread and butter of higher education. If students are unable or refuse to do either one, then it seems to me that a course becomes little more than an exercise in entertainment. In my case that’s disastrous because—and I’ll be the first to admit it—I’m a lousy dancer, singer, and comedian. Here’s the list, complete with short course descriptions: |

||

history 126. western civilization since 1648 |

||

There’s one thing I’ve learned about offering this course each and every semester. And that is it’s the most difficult one I teach. Think about it: studying over 350 years of numerous nations and empires rising and falling, one political upheaval after another, vast social and economic transformation, rapid cultural turnover—all in one semester? Offering this kind of course requires that you choose your battles. Thus I’ve elected to focus on the development of the state from 1648 to the present, albeit in concert with how this transformation affected the governed. Why the state? Since 1648 government has grown enormously (arguably for both better and worse), gradually becoming so much a part of the human experience that it now affects every aspect of one’s life. Yet most people today take the state as a given, seemingly unaware that its extensive presence took much time and many circumstances to develop. This course’s essence, as I teach it, is about how the once-diminutive state became the behemoth that it is now, what role this transformation played in events in Europe and beyond that unfolded over the past 350 years, and what this meant for people subjected to it. |

||

history 310. crime, policing, and punishment |

||

I taught this course for the first time in the fall of 2012. I enjoyed this new offering because the topic appealed to many different students, including History majors, History minors, and more than a few Law Enforcement and Justice Administration majors. The course focuses on the development of criminal justice as we know it today: the committing of crimes, criminal codes and courts, professional policing, and criminal punishment. Specifically explored are questions about the changing definitions of crime, the transition of policing from self-regulation to professionalization, and the adoption and rejection of different criminal punishments, including torture, execution, and incarceration. Broadly speaking, most of today’s criminal justice systems in the world are based on one or a combination of three historical models: those of continental Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States. History 310 considers how and why, from a historical perspective, this is so. |

||

|

||

history 326. old-regime europe, 1648-1789 |

||

I consider this course the most pivotal in my teaching repertoire. That’s because it serves as a vital link between History 126 and two of the 400-level courses I teach. Offered for the first time at this level in the spring of 2011, this course focuses on a basic question that nonetheless has a complex answer: how did the world become “modern?” Suggesting that much of the transformation occurred in Europe from 1648 to 1789, the course explores the specific ways by which this happened. One way indicated by the course, for example, is the development of coherent and centralized government. Another is the emergence of a new culture marked by empiricism, rationalism, widespread literacy, new media, sentimentality, and beliefs about human progress and perfectibility. Still another is the appearance of a globalized market brought on my Europe’s political, economic, and cultural interaction with other parts of the world. A final one is the rise of a “public sphere” in which many citizens grew more conscious of politics and in the process saw themselves more as equals. We explore these phenomena, in part, by examining primary documents regarding two specific developments: absolutism under Louis XIV in France from 1643 to 1715; and the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century. |

||

|

||

history 426 (g). the enlightenment, 1721-1784 |

||

This course was offered for the first time in the spring of 2014. If you’re an undergraduate or graduate who likes to explore ideas and culture, as well as the impact of these on a society over time, this is your course. Having an expansive view of the Enlightenment, I conceive of it as a “cultural revolution” from the bottom-up and distinguished by not only a republic of letters among philosophes and salonnières but also social organizations promoting reform, the emergence of new media, mass literacy, and public opinion, as well as the cultivation of a new sentiment and sensibility in keeping with the "civilizing process." Fully understanding these phenomena nonetheless requires some knowledge of eighteenth-century politics and state craft, social orders, religion, international rivalry, and global exchange. Thus the first part of the course places the Enlightenment within a broader historical space, while the second considers the revolution’s specific texts and ideas. Given the level of the course, I teach it seminar-style and help each student write a research paper focused on Enlightenment texts. |

||

|

||

history 427 (g). the french revolution and napoleon, 1789-1815 |

||

Related most directly to my own research and writing, this course is a personal favorite. Yet I also find it the most frustrating to offer because one can’t do justice to such a complex event within the span of one semester. In spite of this, I try to address key questions about the Revolution: why it began when and how it did; how and why its goals and very character changed as it unfolded; what its national and international repercussions were; and what Napoleon’s relationship to the Revolution was. When offered again in the spring of 2015, I will once more include a focus on an often overlooked yet critical revolutionary development: the ultimately successful slave rebellion in France’s colony, Saint-Domingue (today Haïti). Considering slavery, the revolt, and emancipation in Saint-Domingue not only underscores the Revolution and Napoleon’s broader impact; it also shows how citizens variably understood and applied the revolutionary idea of “liberté.” The course itself will be divided into three parts: 1) taking account of the narrative of events; 2) engaging many of the most crucial primary documents from the period; and 3) doing a research or historiographical project whereby each student chooses a topic of his or her own interest and produces a paper on it. |

||

|

||

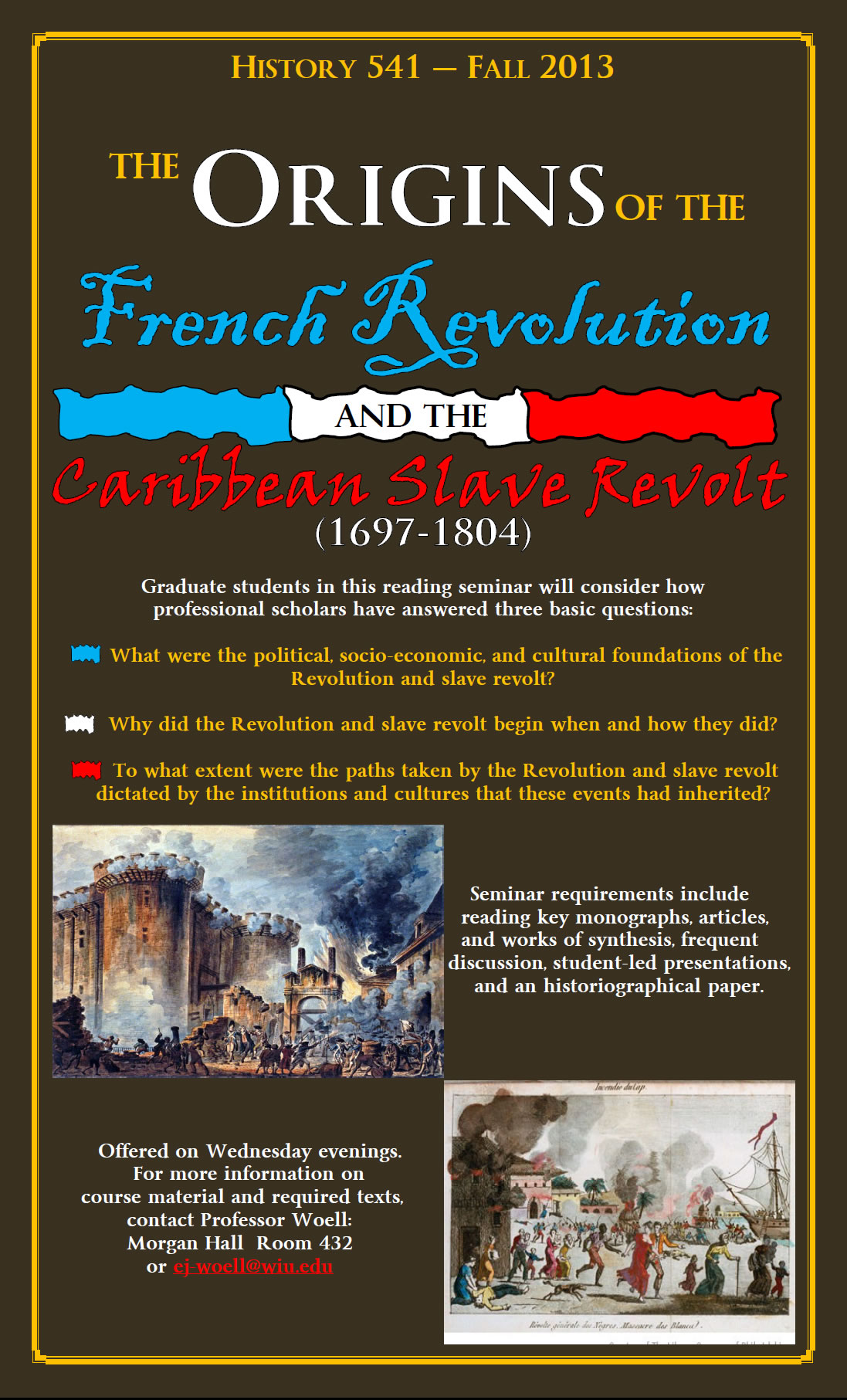

graduate courses |

||

Like most of my colleagues in the History Department, I offer graduate courses at both the 400 and 500 levels. Two of the courses above, History 426 and History 427, can be taken for graduate credit, as signified by the “(g)” placed after their titles. In such cases graduate students are expected to fulfill not only undergraduate requirements, but additional ones in keeping with their graduate status. This means mastering not only the key facts of the Enlightenment in History 426, or those of the Revolution and Napoleon in History 427, but also the long historiographical legacies left in the wake of both events. Since coming to WIU I have also offered numerous sections of History 541, “Readings Seminar in European History.” Devoting the seminar to Europe’s sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, I’ve chosen a variety of topics crucial to this period: rituals, symbols, and representations on two occasions; religion, science and enlightenment on another; and the phenomena and perception of violence on still another. In such a seminar graduate students consider what the history suggests about the topic, as well as how historians have approached it through their methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and scholarly narratives. Most recently, my section of this course has focused on the varied origins of the French Revolution and of the revolt of slaves in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. |

||

|

||

|